That’s right. Not China. Switzerland. So you’re not talking about the much-lamented loss to China of union scale, blue-collar jobs from the fetid factories of America’s Rust Belt? No. So perhaps you won’t bore me with another rendition of that tiresome “America in decline” narrative parroted by gauzy-eyed revisionists who forget how America (like many industrial economies) polluted its way to prosperity in the first half of the 20th Century?

Nope. Like me you may be old enough to recall the choking air of Gary, Indiana, the birth defects of Love Canal, and one that even the Chinese haven’t topped: a river that actually–and regularly–caught fire. Ohio’s Cuyahoga River, according to a 1969 Time magazine article, “oozes rather than flows.” A person unlucky enough to fall into it, said Time, “does not drown but decays.”

No, we don’t want those jobs back because, round about the early 1970’s, Americans decided that they had become prosperous enough to value–and afford–a healthy environment. Getting there, of course, means environmental regulation, which makes things more expensive to manufacture here. So since we all love to shop at Wal-Mart and enjoy low prices, we now let other people make our stuff–cheaply. Those other people can pay their workers much less and they are far more relaxed about the environment. So take a deep, healthy breath and exclaim “good riddance” to all of those “great” U.S. heavy industries and manufacturing jobs.

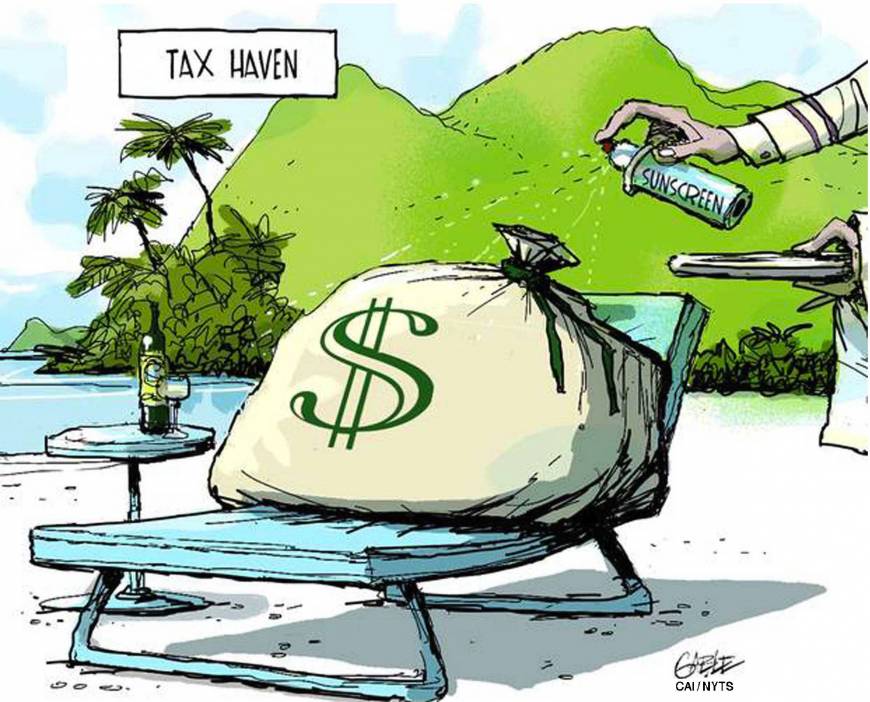

What I am talking about in this article is the tens of thousands of high paying executive jobs that have been quietly exported–in the name of lower corporate taxes–to the squeaky-clean towns near Zurich, Switzerland. It’s a breathtaking migration of people and corporate assets that is costing the U.S. billions in lost wages and corporate taxes every year.

You have heard about the likes of Google and Apple hoarding enormous piles of cash in their offshore companies and paying scandalously low corporate tax rates. Hauled before congressional and Parlaimentary committees, surrounded by stiff accountants and lawyers, the CEO’s always state that their accounting practices are entirely legal. Perhaps. Still, according to some estimates, U.S. companies are holding more that $1trillion offshore, desperate to avoid repatriating cash to the very country where the revenue was primarily earned.

So you hear the politicians talk about closing tax loopholes and raising corporate tax rates. But little is said about the jobs that are off-shored to make it possible for these American CEO’s to claim colorable legality.

Off-shoring jobs to avoid U.S. taxes is an accepted business practice that arises from the language and enforcement of the U.S. Tax Code. Merely raising corporate tax rates on all U.S. corporations–including companies that don’t have the global footprint and accounting muscle to get out from under the high U.S. corporate tax rates–won’t help. The solution is to reform the U.S. Tax Code so that companies aren’t incented–legally–to set up sham companies to avoid U.S. taxes.

I am not talking about Mitt Romney’s P.O. Box in the Cayman Islands. I am talking about hundreds of employees “working” in Switzerland and other tax havens for American companies for the sole purpose of lowering the company’s U.S. corporate tax liability.

Let me explain. Imagine that you are the CEO of a publicly-traded, U.S.-based corporation. Your company may have operations and a bit of revenue trickling in from other countries, but most of your revenue comes from dollar-denominated sales in the U.S. In one sense, that is a good thing. You have only one currency to count and your company’s products and services receive the pricing benefit of a prosperous, stable–if not somewhat moribund for the moment–U.S. economy.

In another sense, those U.S. sales are a huge liability. You’re getting hammered by the relatively high U.S. corporate tax rate. So, isn’t everyone, you ask? Well, what if I told you that some of your competitors are paying a substantially lower U.S. corporate tax because of creative–and legal–things they are doing with their foreign subsidiaries?

Interested? Well, if you aren’t your board might ask you to consider a career in agriculture. If everyone is doing something sneaky (and legal) in a competitive global marketplace then you really have no choice, right? Wrong. What’s happening is not right for the companies concerned because it rewards deception while creating nothing of value. It is certainly not right for the U.S. Treasury. Yet the broken U.S. Tax Code encourages and legalizes what is, in essence, dishonest–and legal–foreign tax avoidance behavior. The system must be changed.

Here is how the system works. The tax “science” involved is called transfer pricing–to many a black art. It is practiced by a relatively small group of highly-compensated tax consultants from the usual firms. Transfer pricing and the tax treaties it functions under allow multi-national companies to lower their total corporate tax profile by attributing revenue from a high tax jurisdiction (like the U.S. or the UK) to a country with a lower taxation rate. Here’s the kicker: in order for the fiction to operate legally, the parent company needs to “sell” taxable assets to its subsidiary company in a low tax country, say Switzerland or Ireland. Then the people in the Swiss company “own and manage” those assets on an ongoing basis, whilst making those assets available–for a price–to the parent company’s U.S. customers.

Imagine sending your CFO to Switzerland to meet with the authorities of several cantons (counties) in and around Zurich. They all want you to site your company in their canton. They like the foreign tax avoiders, whose workers are healthily underworked, well behaved, educated and prosperous. The companies they work for pay their taxes and meet their obligations–something very important to the Swiss. The tax rates the Swiss offer are very competitive. Indeed, some companies have moved their Swiss AG’s two or three times in an effort to secure the lower tax rates offered by neighboring cantons.

Let’s say that our CFO’s visit went well and pretty soon your company has chosen a canton, hired a real estate consultant, and entered into a lease for some suitably impressive office space in a building overlooking beautiful Lake Zurich. You retain a Swiss accountant, a Swiss lawyer, hire a Swiss office manager. You build out your office. You buy furniture, rent copiers and telephones. You contract with a janitorial service and hire several English-speaking office assistants. Pretty soon you are spending lots of Swiss Francs, but you’re still not done.

“Jesus is Coming, Look Busy” goes the bumper sticker. So it is with the IRS. If you have set up a Swiss company to avoid U.S. corporate taxes you must impress the IRS with your piety and industry. Under the relevant tax regulations and treaties, in order for your company to reap tax benefits, it is not enough to merely have a Swiss address. You need to have people–lots of them, all with believably senior resumes, drawing nice packages and sporting impressive job titles–looking very busy “owning and managing” the taxable assets (technology, information) that the U.S. parent has “sold” to the Swiss subsidiary in an “arm’s length” transaction.

It’s all a big show. If done correctly it is legal. Hundreds of U.S. and UK companies are doing it right now. Most of these companies have little or no market presence in Switzerland or the other offshore havens. They are simply there, in collusion with the local and national government, to get a lower tax rate on revenues earned in their home market, which alone justifies the millions of dollars pumped out of the U.S. and into the Swiss economy to maintain the Kabuki theatre. They may shrug and say, “well, it’s legal,” but no self-respecting tax or finance professional will tell you it’s not dishonest.

What’s worse, it sends high-value American management jobs overseas to merely “look busy.” These expats have their homes purchased by the company or managed for them while they are overseas. They have their stuff shipped or stored at company expense. They get nice apartments in Switzerland and send their kids to private international schools–all on the company. Generous car and travel allowances permit them to travel extensively in Europe or go home frequently–all in the name of less tax.

[Note: But Americans will always be, well, so American. One Texan from a company I know wanted to have his Chevy Suburban shipped to Switzerland. No one in HR, apparently, told him about the high gas prices in Switzerland, the narrow streets in Europe or the likely frowns of the hyper-vigilant Swiss. Yes, the Swiss do like the “free” corporate tax they get from your company and the cash you spend in their shops and restaurants, but they don’t like gas-guzzling American cars and aren’t above tapping on your car window and wagging their finger if they catch you warming up your Chevy for too long on a cold winter morning in Zug.]

But I digress.

There is a lot of talk in Washington these days of raising tax rates charged to U.S. corporations. That won’t fix the problem. What those well-intentioned people need to understand is that given the choice between paying a high tax and spending the same amount on high-flying accountants to avoid the tax, corporations will choose the latter every time.

What we need is a U.S. corporate tax policy that doesn’t reward companies for off-shoring high value jobs just to keep from paying tax rates that are out of whack with the rest of the developed world. Bring those Americans home. They will be much happier with their baseball and Chevrolets. Let the Swiss go back to what they do best, which–call me simple–always seems to involve money and a bit of high-minded finger-wagging.

DM