In the week leading up to the recently concluded Third Plenum meeting of the Chinese Communist Party, the Supreme People’s Court, China’s highest court, issued a white paper recommending that the government “implement the courts’ independent exercise of judicial authority based on constitutional principles.” If that wasn’t enough to get your attention, the Court asked the government to support this proposal by eliminating “power, money, allegiances, relationships and other extrajudicial disturbances.”

“Golly,” a Chinese lawyer friend commented, half seriously, “how on earth would they make their decisions?”

In the end the desired judicial reforms did not appear from that meeting. What we got instead was a commitment to substantial new economic reforms, a certain relaxation of the one-child-only and policy, and the elimination of labor re-education camps.

Proposals for greater judicial independence in China have been floated, in one form or another, many times in the past. Perhaps I should not take them very seriously. But I really believe that judicial reform is the Next Big Thing in the Chinese government’s quest for stability and legitimacy.

[Full disclosure: my interest in Chinese judicial reform began in 2007-08 with a rather more commercial objective in mind. I was living in Beijing, leading the Westlaw China project for Thomson Reuters, the world’s leading legal publisher. My job was to do what I had previously done in the UK, Germany and a few other places–build and launch a local-language online service that lawyers use to research the law.]

What got my attention, and what makes the Court’s recommendation so important, is not just the level at which the statement surfaced–but in its timing: in a pre-Plenum white paper. Can I be forgiven for thinking that the conditions necessary for serious judicial reform in China are now, finally, beginning to coalesce?

The Chinese government is keen to preserve and grow the legitimacy it has earned through three decades of fabulous economic—if not political—reform. But alongside the economic growth that has positively impacted virtually every sector of Chinese society, there is also runaway inequality, breathtaking abuses of power, and, recently, a seeming inability to control unprecedented environmental contamination. These chip away at an unelected government’s hard-earned legitimacy.

We are presented with the spectacle of an absolute government more insecure, more stability-obsessed, more legitimacy-craving than the western governments we know—ones that are run by people who could be thrown out of work in the next election.

Some people point to the American system of government and state flatly that legitimacy only comes through the ballot box. With all due respect to the well-meaning pro-democracy communities now active in China, the answer is not elections–at least not yet.

More elections will eventually come to China, but in China’s ancient culture no one is entitled to anything. Rights and powers are conferred—usually from above—and are not innate. People in such a culture actually derive certain comfort from knowing their place in a highly stratified societal hierarchy. The Confucian, collectivist soil of China is a tough place to plant the seeds of messy, noisy, bottom-up democracy–the kind that Americans always think everyone else wants.

If you have raised an eyebrow, allow me to ask whether you believe the recent spectacle of a U.S. government shutdown and threatened debt default (remember who holds much of that debt) received balanced coverage in the Chinese media? Do you think the nightly warbling of Boehner and Reid won over any converts to our system of representative government? It works for us—sort of, lately. But not for China.

The Chinese still want many things that we have. But they actually don’t have a problem with basic social inequality, or even a big, all-powerful, unelected government. All they ask, in exchange for masters not of their choosing, are three things:

-continued economic opportunity and growth;

-a reasonably healthy environment in which to raise their only child;

[it wouldn’t hurt if the government elite—especially at the local level—bloody learned to behave]; but most importantly,

-Simple Justice.

Yes, simple justice. What the Chinese people want, oh so much more than democracy, is a judicial system that is fair and impartial. I am not talking about correcting the inequalities that pervade any single-party political system. Party members—who form a tiny minority of the Chinese population, will continue getting all the good stuff—the jobs, the dwellings, the cars, the mates.

I am talking about a system that resolves the simple disputes that arise out of a society with an exploding, burgeoning commercial class filled with people who have galaxies more property (and the desire to keep it) than Chinese people of, say, twenty years ago.

Forty years ago in China only the government and powerful party functionaries owned significant property. Now even average citizens have their own cars, apartments, houses. They even buy and sell securities, investment properties, etc. How do they resolve their inevitable disputes?

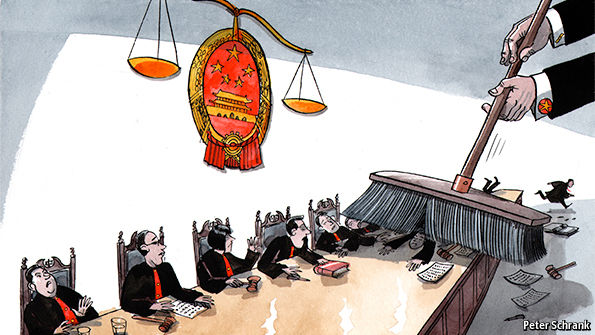

Probably not in China’s courts. Today, the only way to achieve “predictable justice” in a Chinese court is to bribe the judge. And if you are well-connected in the Party, so much the better. Would you willingly submit your property or contract dispute to a court that you know is likely to be influenced by personal connections, money or politics?

This is actually something rather basic: impartial and efficient judicial resolution of the hundreds of thousands of private disputes that arise between Chinese citizens. The Party is not in the room as justice is dispensed. Just the people, the facts, the law and the Court.

I propose the English model. The English began building their greatest gift to the world–an independent judiciary–in the 11th century by focusing reforms in lower courts, ones that (1) did not deal with criminal matters, and (2) did not adjudicate the rights/property of the powerful elites: the Crown, the propertied class, the Church.

Following this example, Chinese reforms to judicial administration and the rules of judicial conduct could begin in courts that adjudicate only matters between private citizens. The goal is to create a perception of fairness so that the people won’t continue undermining the court’s legitimacy by resorting to “extrajudicial disturbances.”

This is more judicial reform than political reform. The English had reasonably independent magistrates meting out basic justice between private parties (and thus lending legitimacy to the Crown) centuries before representative democracy leveled the political playing field.

In tribal societies the legitimacy of the chief is maintained, in no small part, by the fairness and wisdom he displays in resolving disputes between his people. Legitimacy through political reform (of the electoral variety) remains a ways off in China. But if the government reforms the judicial system into a reasonably fair and impartial arbiter of disputes, isn’t this really the low hanging fruit of civil legitimacy?

Next week: How Chinese courts resolve disputes, and then how they explain and propagate the rationale for their decisions, can be the stability and legitimacy-creating agents that the government desires.

Follow me on Twitter @takeitglobal